“For much of the world’s biodiversity it is in fact the end of the world. ”

Without doubt, there is an ominous note in the title of The Atlas for the End of the World. But there is truth also, and along with it a treasure trove of insight and information of incredible value for any photographer seeking to chronicle the problems facing our planet, as well as the hard-won progress and possible solutions.

If the title is provocative it seems clear the authors (University of Pennsylvania landscape architect Richard Weller and his colleagues Claire Hoch and Chieh Huang) think the world needs a little provoking. To understand why requires some history.

For inspiration this Atlas harks back to the very first Atlas published in 1570 by Abraham Ortelius in Antwerp, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. At that time the countries of Northern Europe where hot and heavy into the world exploration and dominance game, and Ortelius showed them way. If his Atlas had a few vague (or empty) spots, so much the better. Who knew what riches awaited exploitation? The world was vast, limitless, and bountiful.

That didn't last long.

Now just 450 years later we see limits everywhere and biodiversity is under siege, often crippled by human growth. If Ortelius' Atlas marked a great beginning for humans, then for many endangered species this Atlas marks the end of their world. Hence it's title.

Weller (and his apparently tireless co-workers) have accomplished something massive: a series of 44 maps that lay out most of the world's environmental problems, complete with essays on each subject – and access to the underlying data. For any environmental photographer seeking guidance it's pretty much one-stop shopping.

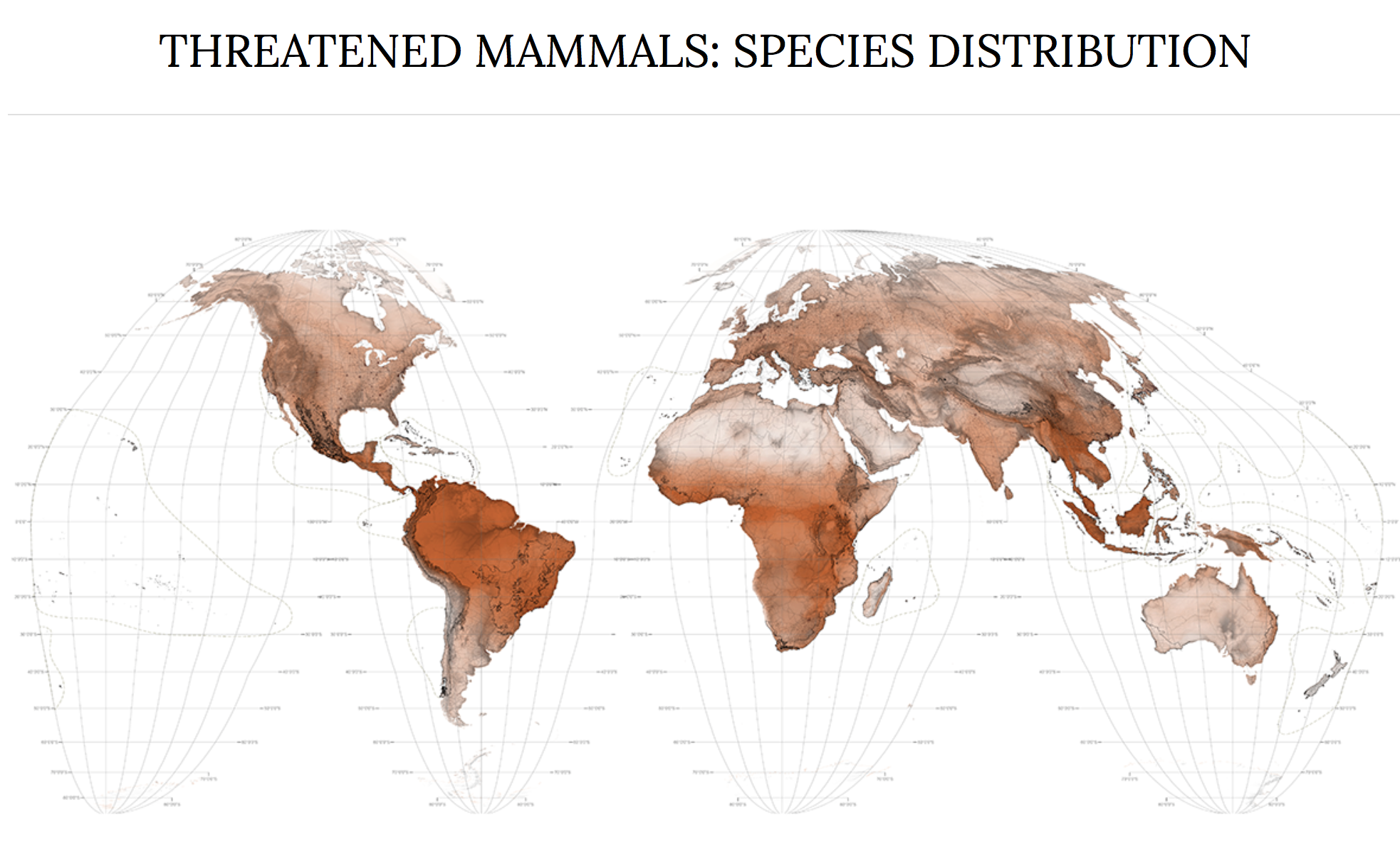

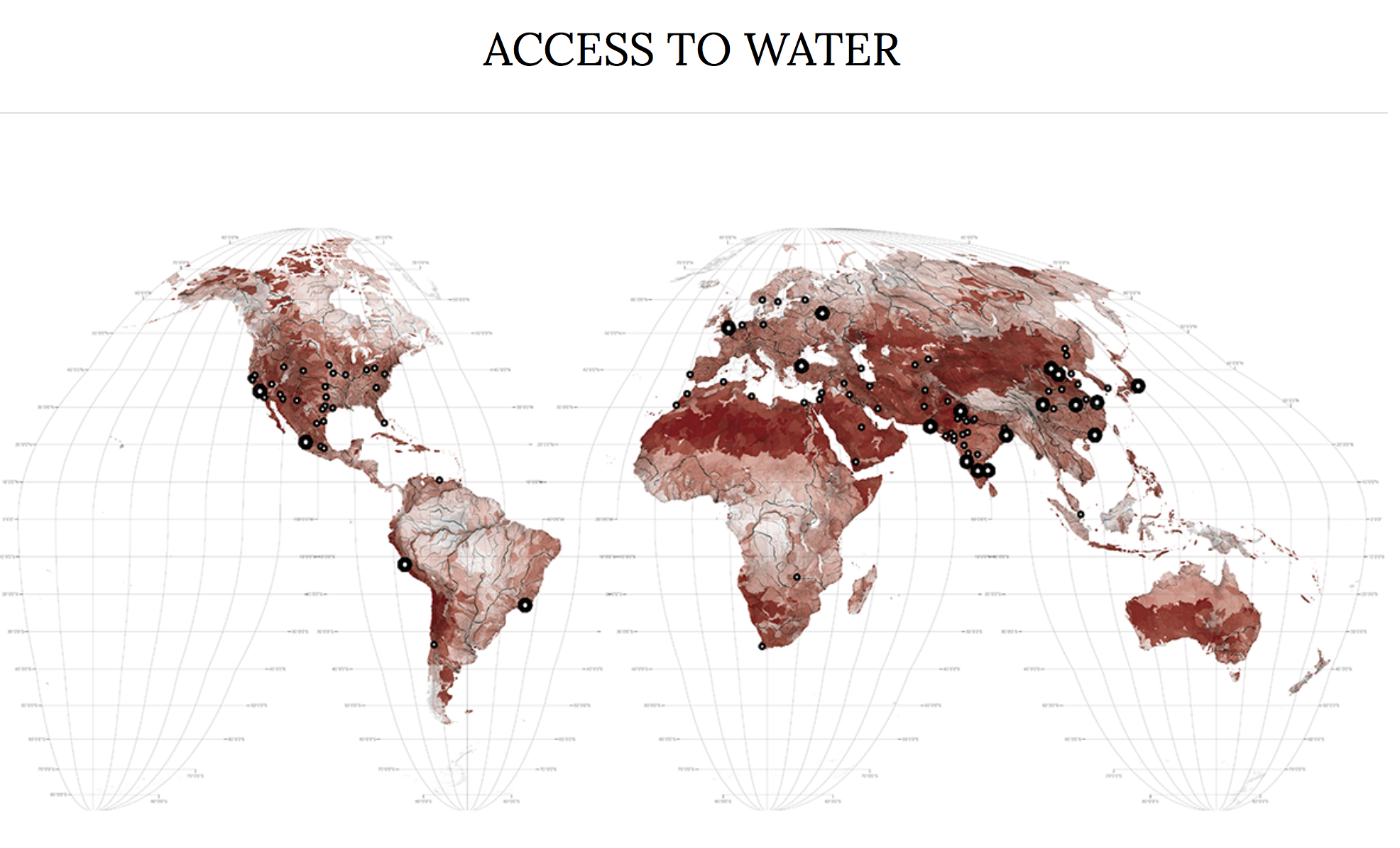

The variety of specific examples is mind-boggling: threatened mammals, locations of impact form rising seas, where population pressures will be greatest. Further digging will find maps chronicling access to water, where environmental displacement is taking place, the intricate web of worldwide megastructures and where corporate wealth is concentrated. And still there is more!

Much of their focus is on the intersection of biodiversity and urban growth, how it will threaten biodiversity as we move towards 10 billion people on earth by 2100. (Actual numbers may vary, but any reasonable observer gets the drift.) Quoting the Atals, "If say an extra 3 billion people move into cities by 2100... it means we need to build 357 New York Cities — 4.25 per year to the end of the century!" Oh!

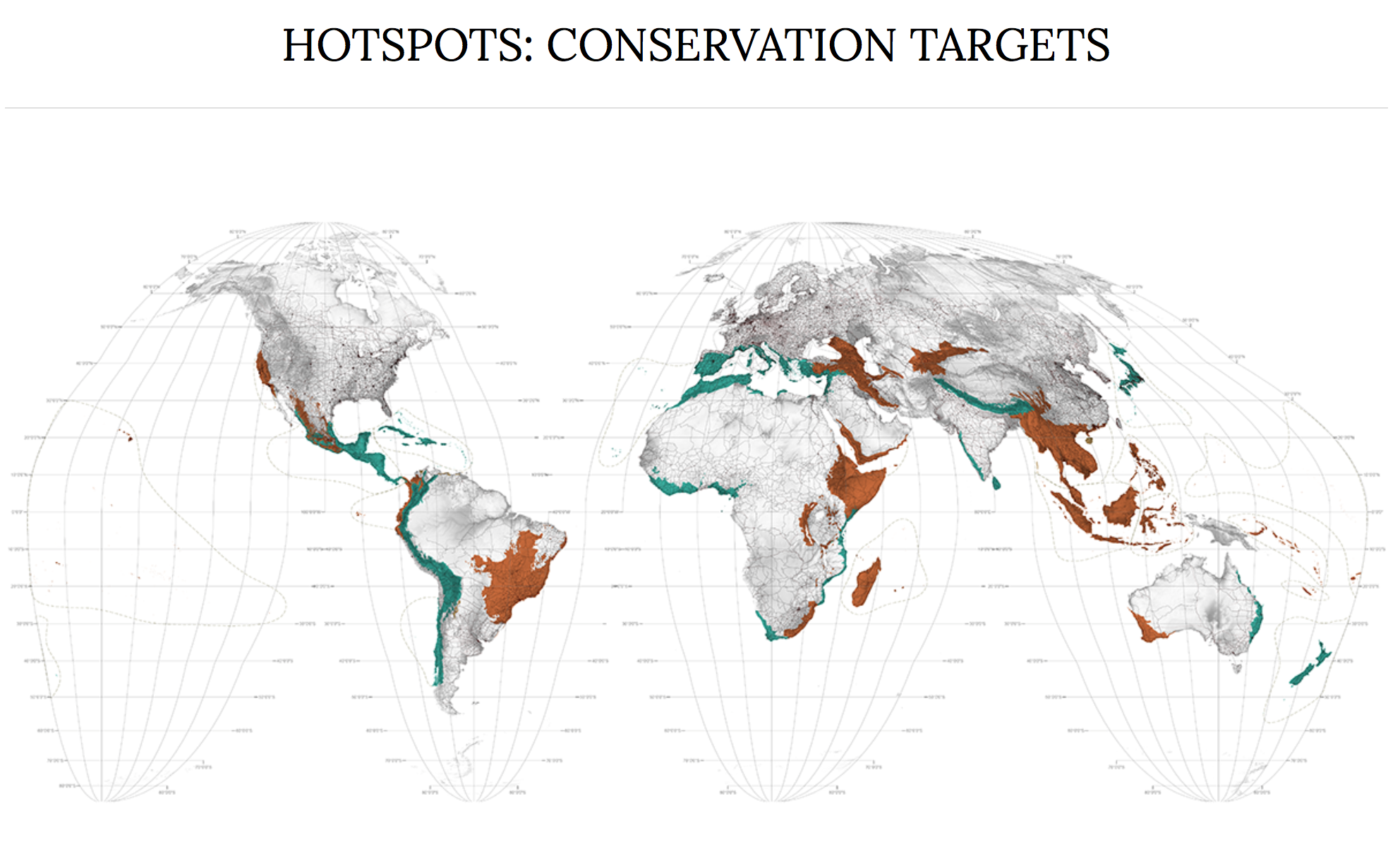

Efforts to stem the impacts to biodiversity were laid out as part of the UN Convention on Biodiversity which seeks to protect at least 17 percent of land within 36 defined hotpots by 2020. How's it going? Not so good. Only 14 of 36 have met their criteria so far, according to Weller's analysis.

Whether the Atlas will provide the needed provocation and leverage to meet these goals remains to be seen. But as a resource it is a stunning achievement already. In places the Atlas covers territory I know well.

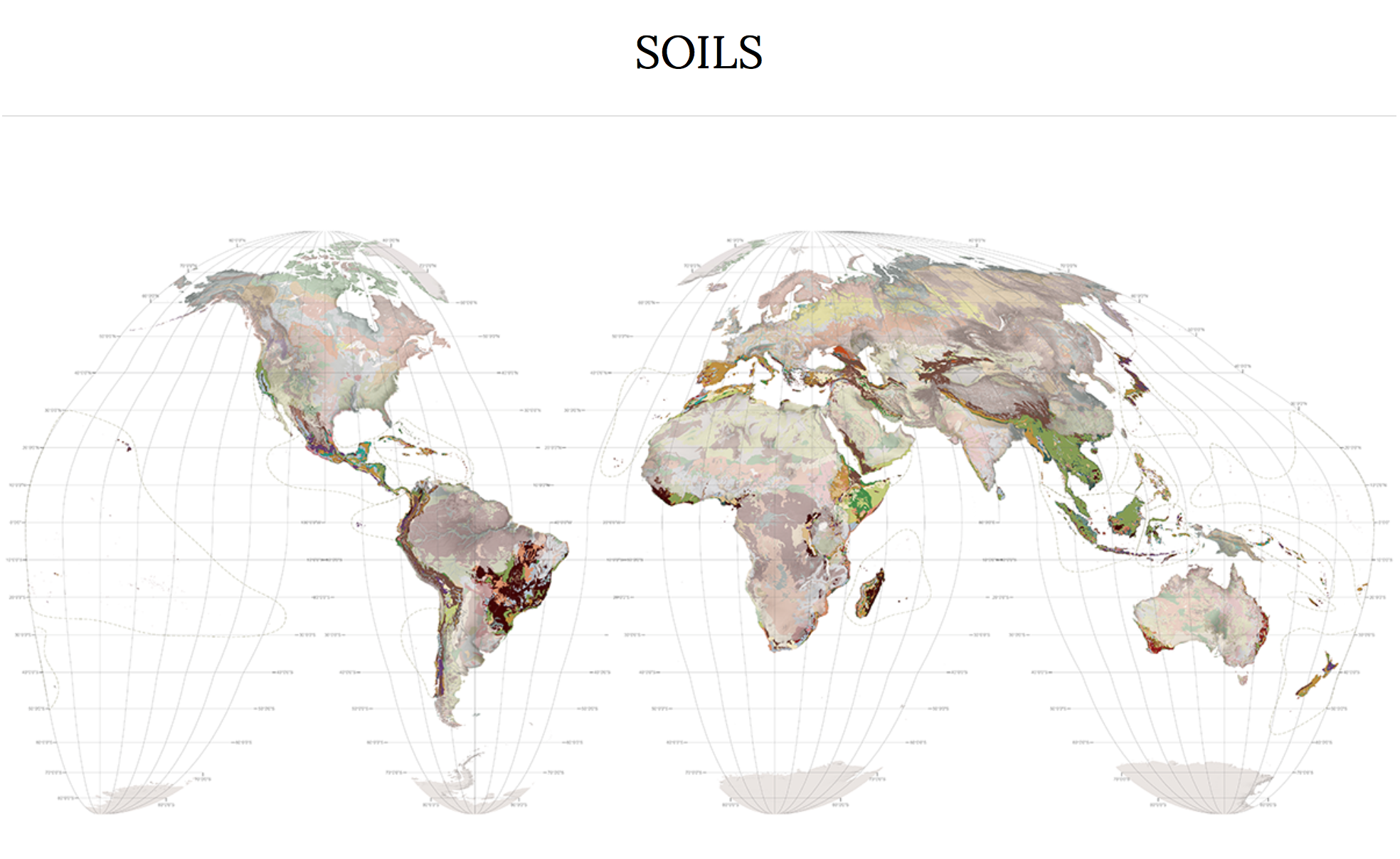

In 2008 Dennis Dimick and I collaborated on a National Geographic story about soil, Our Good Earth. For anyone trying to comprehend the vast environmental consequences of world-wide agriculture these maps offer both range and insight. This includes the map of soils, as well as croplands, meat production, land degradation, and deforestation. As a photographer with limited resources and a whole world to cover this sort of information is priceless.

But for sheer impact I'd point to one of their Datascapes which give graphic impact to the foundational data. This foodscape, for example shows the land needed to feed the planet, comparing land needed today with land needed for 10 billion people in 2100. It's particularly alarming that the graphic shows that we simply don't have that much arable land. Something is going to have to give.

I'll leave the final words to Weller and his colleagues, along with my thanks for valuable work well done.

"Set diametrically at the opposite end of modernity to Ortelius' original, this atlas promotes cultivation, not conquest. As such, this atlas is not about the end of the world at all, for that cosmological inevitability awaits the sun's explosion some 2.5 or so billion years away: it is about the end of Ortelius' world, the end of the world as a God-given and unlimited resource for human exploitation. On this, even the Catholic Church is now adamant: "we have no such right" writes Pope Francis."

Credits

All maps and images © 2017 Richard J. Weller, Claire Hoch, and Chieh Huang, Atlas for the End of the World,

The authors have kindly made this material available for use under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.