From High School USA by Jim Richardson

Part One

We are all Storytellers now.

Once upon a time we used to be plain old photographers, or authors, or journalists. But now in this digital age we have all morphed into a new form of being: storytellers.

In many ways we always were. Storytelling is basic to human communications. It’s how we make sense of our world, how we elevate our existence, give it meaning. For much of human history stories were told in words, first spoken and then written. Pictures have always told stories, to be sure, but in this new (and fresh) digital realm pictures have become a language of their own. Pictures have enlarged their realm of influence, taken over much of our day as we scroll Instagram’s endless stream and thus come to dominate the online sharing of experience that now dominates everyday life.

So now visual storytelling has become essential. Heretofore the arcane business of telling stories in photographs was the province of a small cadre of specialists — photojournalists being one example — who had access to the printed page. LIFE magazine photographers like Gordon Parks, W. Eugene Smith and David Douglas Duncan come to mind. Access to the printed page was tightly controlled. But now that access to eyeballs is totally ubiquitous. On any given day hundreds of millions of people tell visual stories through Instagram, Facebook or Snapchat.

Storytelling is, at the heart of the matter, about making connections. Events can stand alone, like isolated facts. But a series of events connected and placed in order become a story. Likewise putting pictures together is a signal to viewers that there are connections between them. That’s the essence of visual story telling. Our brains are hard-wired to find connections — we enjoy it, we work at it consciously and unconsciously all day long.

This series is about learning the craft of visual storytelling. After setting the groundwork here, subsequent posts will get down to brass tacks about how to construct a visual story. But first we need to get on the same page about our purpose and goals, a bit about definitions, and some backstory about my explorations into visual storytelling and why they might matter to you.

Putting two pictures side by side is a signal that there are connections between them.

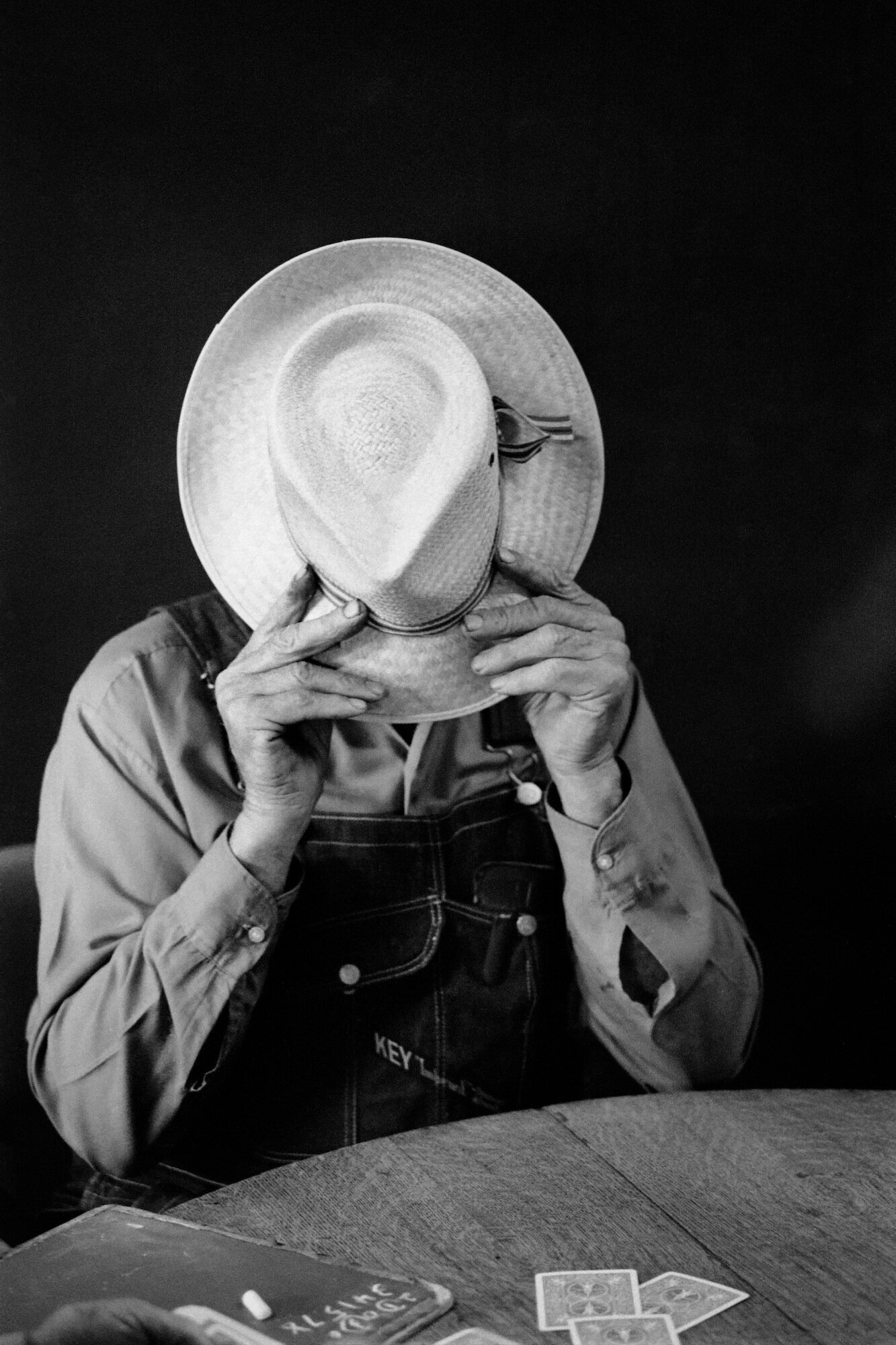

Put two pictures together, side by side, and the viewer is suddenly challenged to see underlying connections, to find the implied meaning. Take as an example these two pictures, the old man shyly covering his face with his hat, and the old woman’s hand on the door, the etching giving her a devilish smirk. Taken years apart, there is no literal connection between these moments. But we find subtle, implied meaning; nothing concrete but somehow fundamental.

Certainly single pictures tells its story. But in combination they take on expanded meaning. LIFE magazine’s famous picture editor Wilson Hicks called this the “third effect.” While each picture says its own thing, together they say something more.

Now take a group of pictures, put them together in a particular order — and in such a way that the grouping implies connections — and you have a picture story. Perhaps the greatest example is the LIFE magazine story Country Doctor by W. Eugene Smith.

Fundamental to our discussion is an understanding of what visual storytelling is not. It is not simply using pictures to illustrate points made in the text of a written story. It is not using pictures as evidence to butress what the story says. Such uses of pictures are valid, but just gluing pictures into a text narrative is not visual storytelling. By contrast Smith’s Country Doctor visual narrative succeeds even if you never read a word of the text.)

In visual storytelling the pictures become the prime actors. They carry the story. They don’t just play a supporting role.

Stories have power because our brains hunger for order. Stories tame the chaos, convert random events into digestible, consumable, memorable packages that elevate life. (Odysseus comes home in the middle of the story to find that his wife has given him up for dead. Where has he been? What’s going to happen next?) Real life goes on randomly, seamlessly and endlessly. By contrast a story has a definite beginning and a conclusive end.

And a middle. But many different paths can connect the beginning and the end. The path you choose through the middle is where narrative happens. Those different paths are the essence of narrative; same facts, different journey.

Narrative also takes place in visual stories. Any given set of pictures can be arranged in many ways. Put the pictures in a particular order and you have chosen one narrative. Change the order and you create a different narrative.

At National Geographic we often take 40,000 pictures for a single story. All those images gets boiled down to about 60-80 that we submit to the editor and about 40 that we work with creating the final layout. My goal in shooting a story was always to have a strong enough set of pictures that we could do the whole story, throw it away and still create a strong story from the left over pictures. It would be different narrative but would still tell the same story.

Why should you care:

Stories magnify your power to communicate.

Telling stories with pictures has been around as long as photography. But now it has transcended it old haunts : movie making, photojournalism in mass market magazines, documentaries attacking social ills. In the Age of Instagram, photography has become an everyday skill, on a par with accomplished writing skills, verging on becoming a prerequisite to modern functional literacy.

However, relatively few have mastered the skills to produce picture stories, longer statements with grander ambitions. It’s a valuable skill. Knowing how to create compelling picture stories will set you apart from other storytellers. And it will reward you with a greater ability to communicate and make a difference throughout your career.

Building visual stories is one of the toughest nuts to crack for many photographers. Beginning students know this for sure, but so do accomplished professional photographers with long careers. The skill to build a cohesive visual narrative out of a set of pictures is rare, and thus valuable.

High School, USA

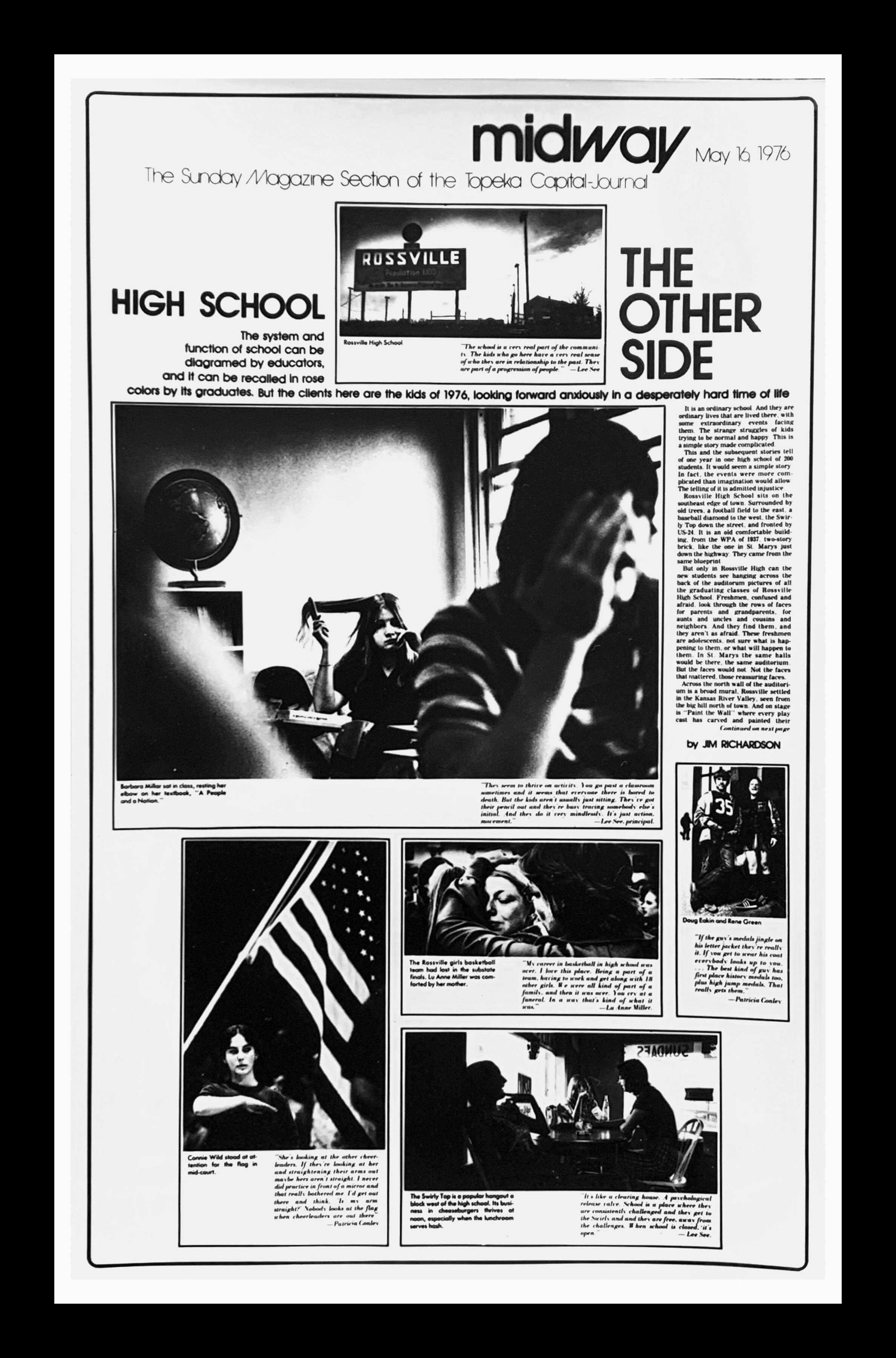

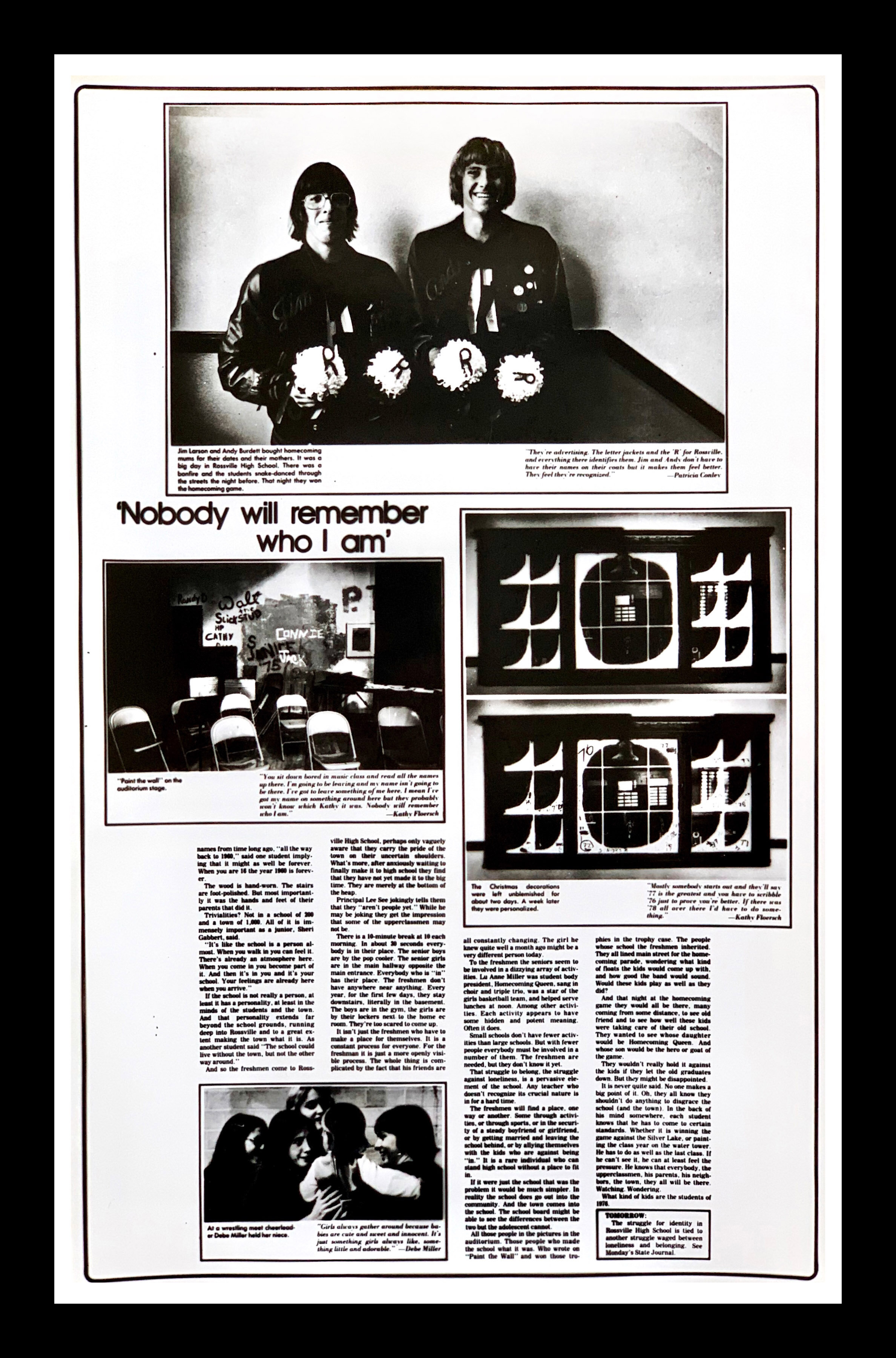

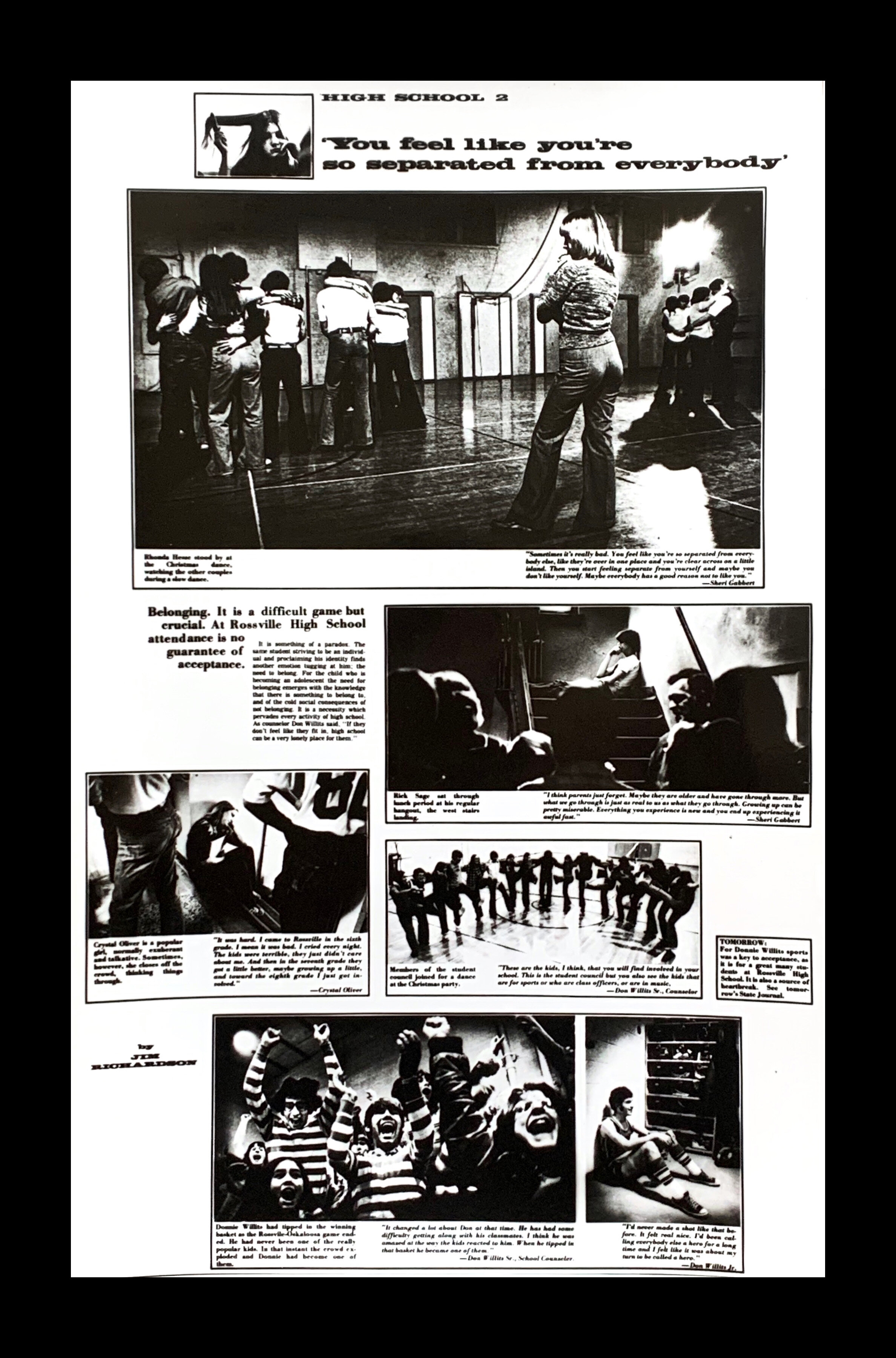

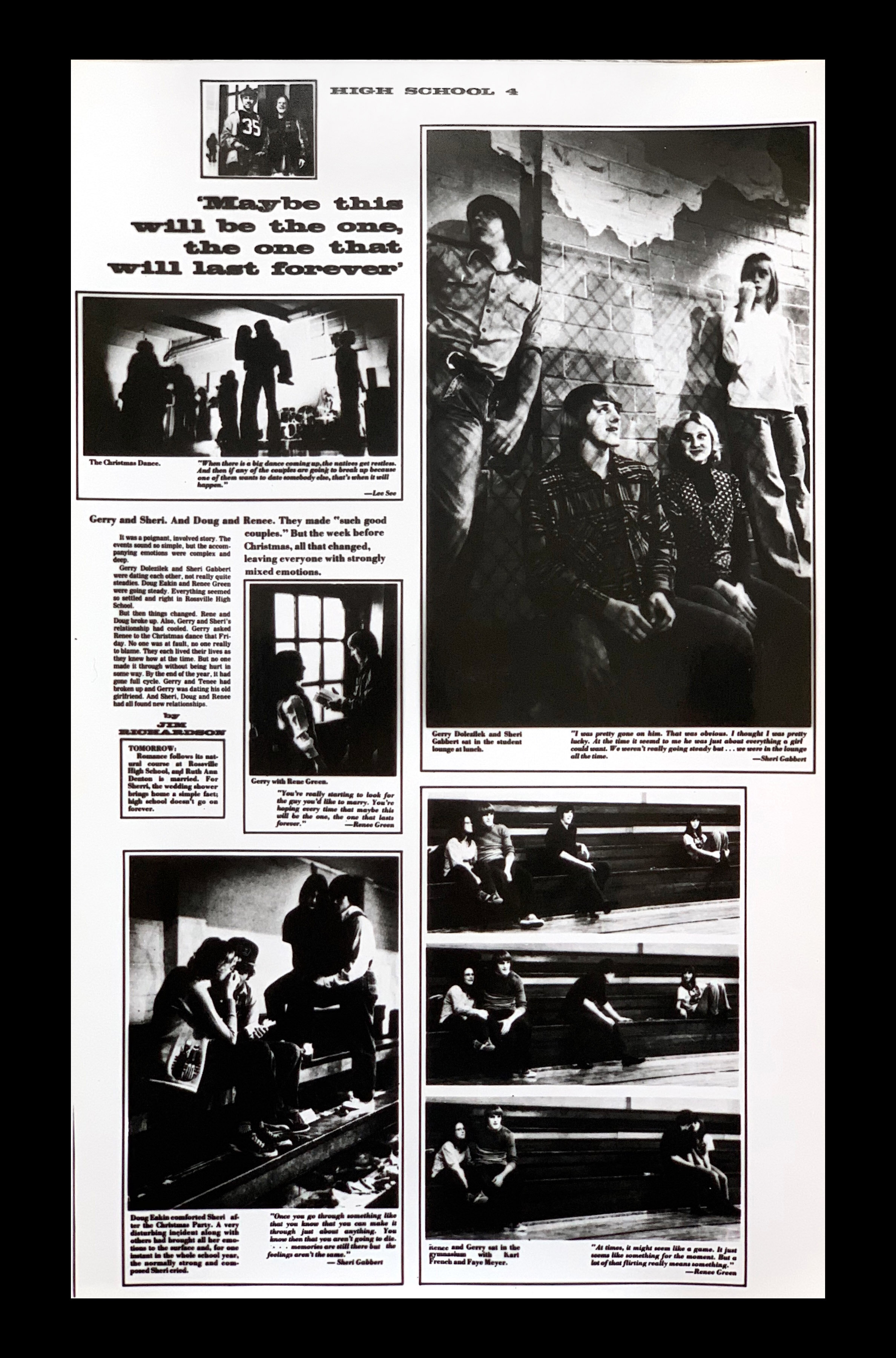

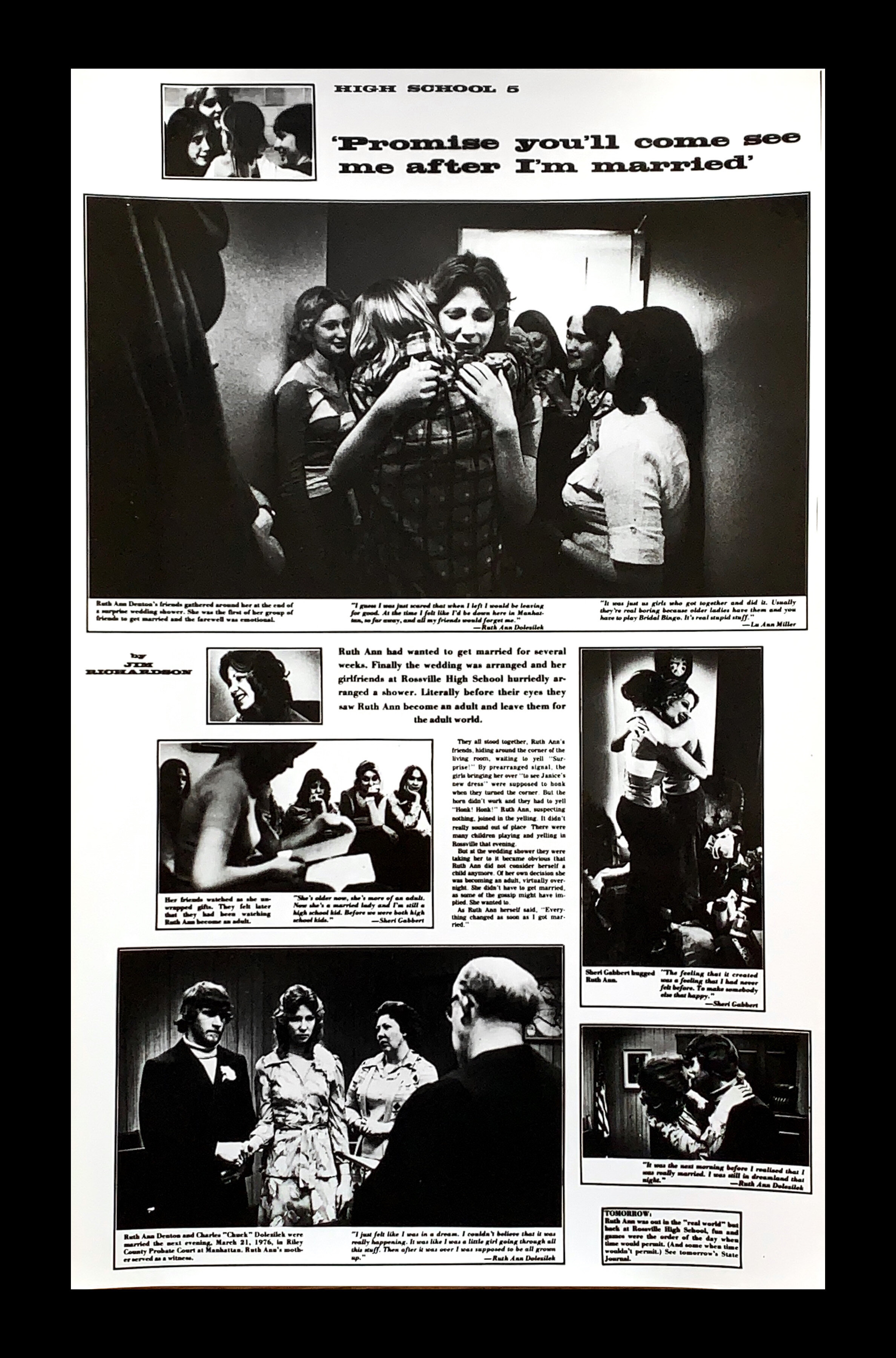

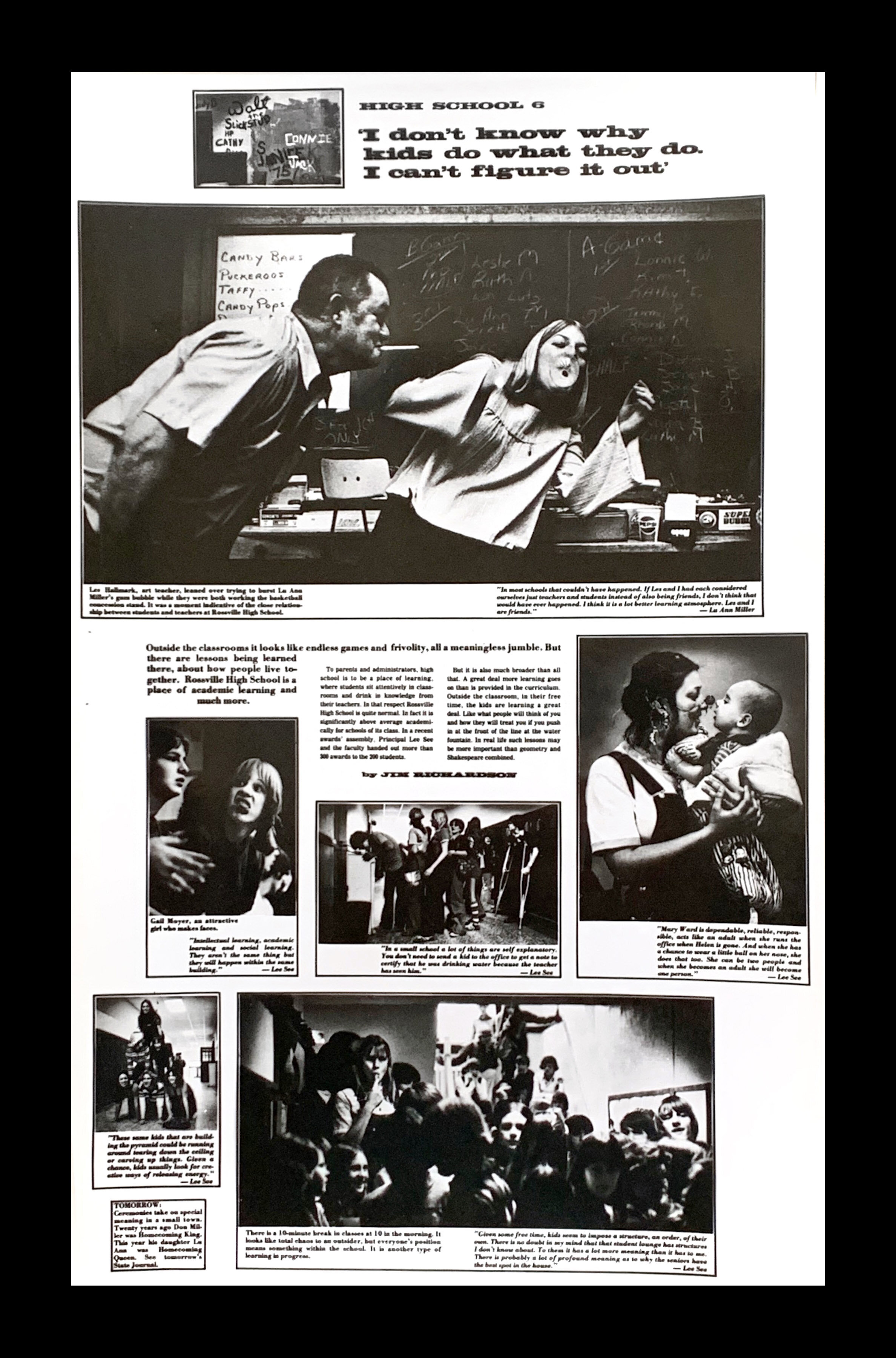

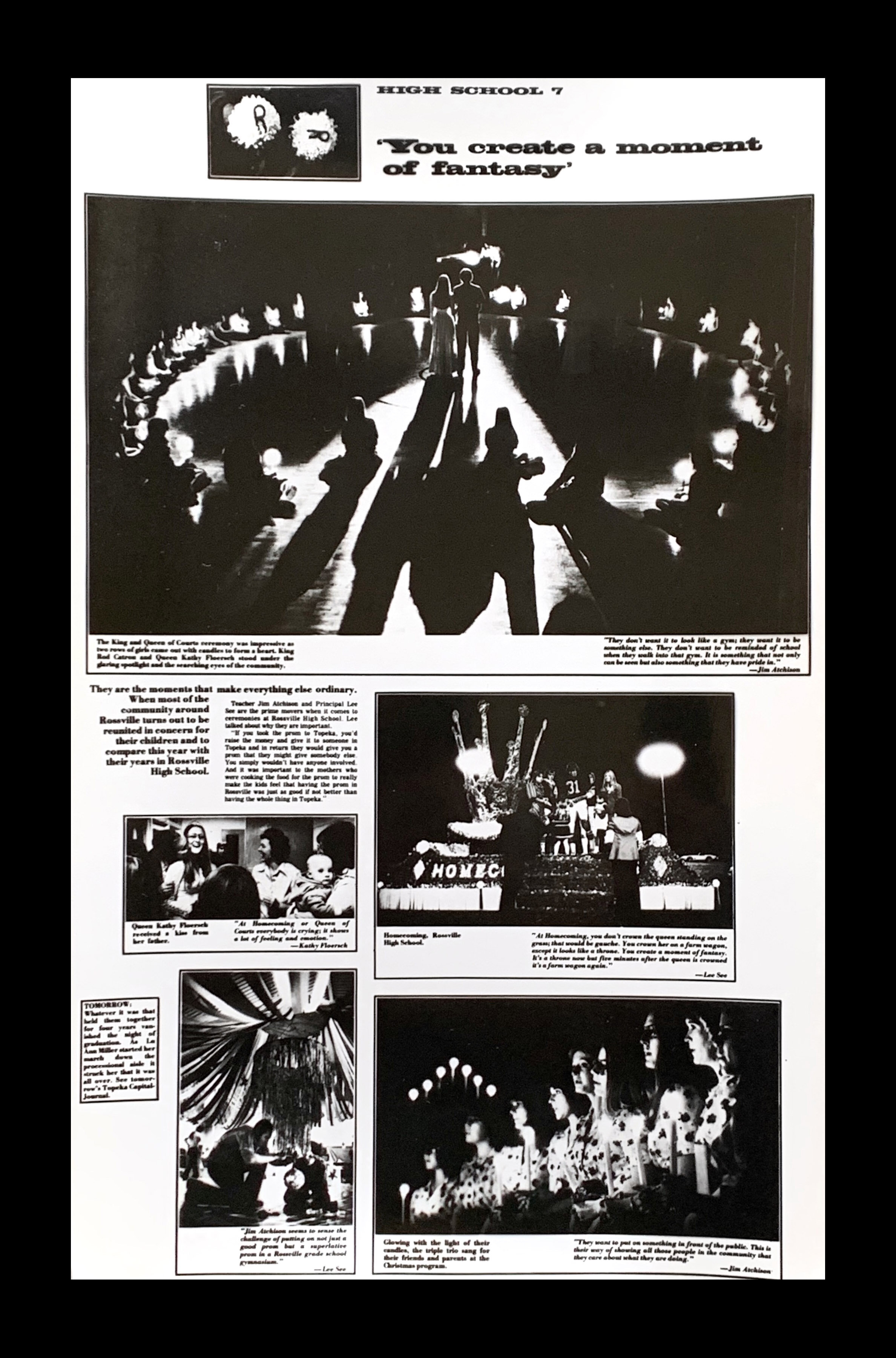

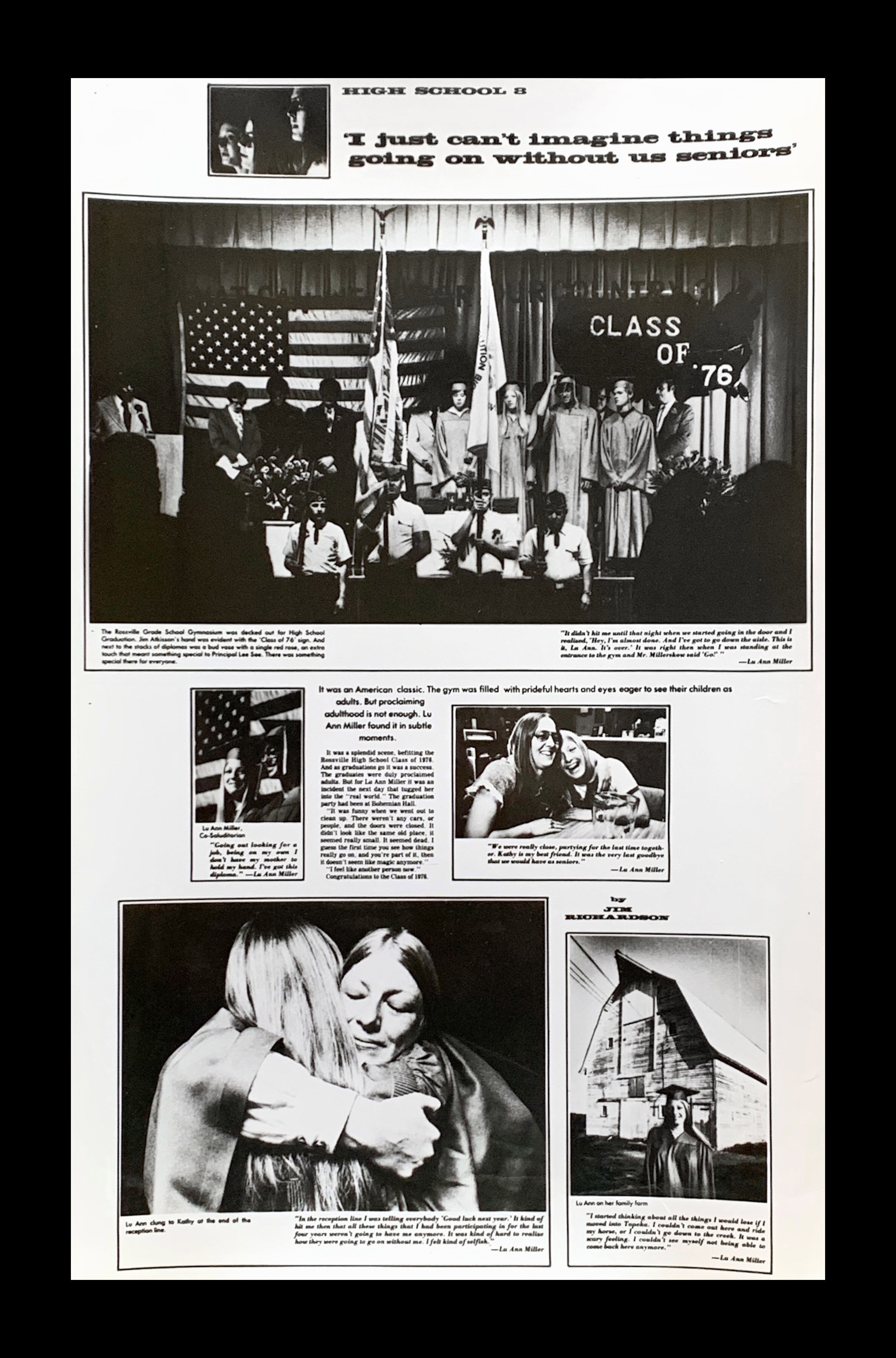

Classic 1970’s newspaper picture layouts from the Topeka Capital-Journal

Why you should listen to me:

My credentials for pontificating on this craft go back a ways. Over my 35 years with National Geographic I did more than 50 stories — not a record, but a lot. Before that I produced 10 photo books, some artful and important, some just grind-it-out long form visual illustration. But before all that came the real training ground: I spent ten years working for the Topeka Captial-Journal under the great Rich Clarkson in its heyday during the 1970s. Among my staff colleagues there were David Alan Harvey, Brian Lanker, Sarah Leen and Chris Johns, to name a just a few. We did picture stories virtually every day. Once (for fun) I figured out that during that time I did 1,000 picture stories.

We did more than just the photography. Under Clarkson we did the layout, wrote the captions, wrote the headline (and set it with press-on type.) Often this was done under intense deadline pressure, minutes sometimes, not hours or days. (One time I got to the office, developed three rolls of film, did the layout, printed the pictures and wrote the captions for a page in 18 minutes total. I’m not kidding. Not my best work but not bad either.)

So from 50 years of experience let me offer you some nuts-and-bolts visual storytelling advice. As close to plug-and-play as I can get. My offerings are not esoteric journalistic or artistic theory. Knowing the theory will not make you a visual storyteller. Actually doing picture stories is the only thing works. You’ll get better at this by applying these concepts to real life situations many times over. You can’t learn to do pictures stories by doing just one.

Ground Rules

First, however, I’m going to insist on one fundamental concept: the picture story — however it is displayed — is the end product. Our goal is the combination of pictures, words, headlines, maps, or whatever that will be our final visual narrative. The picture story is final product, not the pictures themselves. The layout is not a vehicle to display our best pictures. Our pictures are raw materials. The picture story is not a gallery for the pristine display of images. Unless you submit to this basic concept you will always be compromising the final product. We always want to be displaying the pictures so they can do their job as effectively as possible, but when push comes to shove, the integrity and effectiveness of the finished picture story wins out. The picture story is the product.

If you want pristine display of your pictures then do a fine art book. But don’t call it a picture story.

Rather harsh, isn’t it? Yes, it is. Great pictures will wind up on the cutting room floor. At National Geographic we called it (with macabre truthfulness) “killing your babies.” So cry a little, then get over it.

Second, you will be confused. Everybody is. The finished layout or arrangement is the resolution of that confusion. Take some solace from the fact that established professionals wallow in this morass of confusion, wander and get lost, flounder and flail, until something coherent emerges. You are not alone.

With all that said coming installments in this series will begin with the simplest of visual narrative strategies and work forward from there.